As someone who has been playing games for as long as my pudgy little toddler hands could hold a Super Nintendo controller, it’s been interesting for me to see how my taste in games has changed over the years. What started out as an intense love for mascot platformers eventually turned into a deep appreciation for simulation games. Over time, this passion turned to RPGs, and then action-adventure games, often with RPG elements and condensed, purposeful worlds. Yet despite all their differences, there’s a thread through them all that this year’s new releases made me aware of–and I’m now compelled to tug at it.

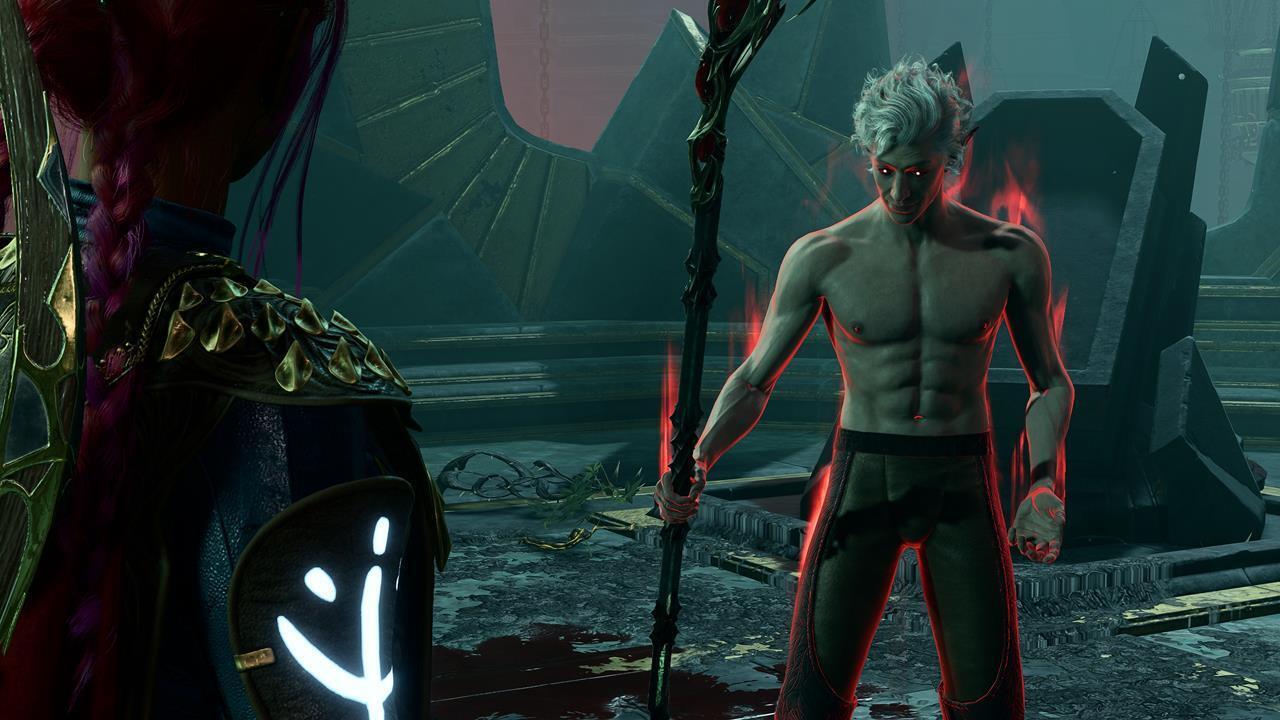

Recently, GameSpot named Baldur’s Gate 3 its game of the year–a choice I heavily advocated for. During our deliberations, I told my colleagues, “I don’t think it’s the most cinematic game this year, or the most ‘artistic,’ but I do think it is the best game.” My second favorite game of 2023 was The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, which, once again, I can admit wasn’t as artistic as something like Alan Wake 2, and lacked the polish and sheer spectacle of Final Fantasy XVI, Marvel’s Spider-Man 2, or Star Wars Jedi: Survivor–though I will argue that descending into the depths was one of the coolest gaming moments of the past year. So, I then began to wonder, “What in my eyes made for a great game?” And while novel concepts, strong mechanics, fascinating characters, and interesting art are all up there, what it really came down to–and what I think some of 2023’s top tiles did best–is give me a choice.

I’ve always loved decision-based games, whether the decision I’m making is my party composition, to build a rollercoaster that will send my park-goers to their doom, or to romance Thane yet again in Mass Effect 2. Fortunately for me, many games allow players a sense of choice and freedom, and more of these games are being made each and every day. But in a year of mind-blowing games, Baldur’s Gate 3 and Tears of the Kingdom won my heart because of how they elevated what “freedom” in a game entails.

Though the types of choices you make in Baldur’s Gate 3 and Tears of the Kingdom are dissimilar–you can’t choose to side with Ganon instead of Zelda, nor are you able to glide on over to Baldur’s Gate before you’ve traversed the Shadow-Cursed Lands–they each offer the player a tremendous amount of freedom. So much freedom that, at times, they feel limitless. Many games, particularly those as large and time-consuming as BG3 and TokT, struggle between feeling overly guided or massive-yet-empty. Yet developers Larian and Nintendo are triumphant in creating lived-in worlds that gently guide you while also giving you permission to do as you please. It’s a wondrous thing to make work, and an even more wondrous thing to experience.

It didn’t take long for me to discover the breadth of Baldur’s Gate 3. After washing ashore and waking my wife–I mean, Shadowheart–and collecting my husband, Astarion, we found ourselves just outside a derelict temple. I was then able to intimidate a pack of looters into leaving (much to my macabre companions’ amusement), enter the temple, use a flammable barrel to send a half dozen enemies to their death, sneak my way around a series of traps, loot a key from a forgotten crypt, and then open a secret passage that awoke a collection of corpses scattered about the tomb. And it was only a few more hours in that I discovered that my epic adventure was actually an incredibly small and relatively insignificant portion of the game.

The game is filled with these kinds of moments and set pieces–with relentless fun and this sense of adventure. But as I progressed through the game, I became increasingly more aware of its depth. I began to save-scum incessantly, not because I necessarily wanted better dice rolls, but because I was desperate to know every possible thing that could happen. Could I truly kill that enemy with a slight shove off a platform? Was it possible to save every last person a malevolent monarch had sentenced to death? And how much damage could a lobotomy do to me really?

Yet when I started my Dark Urge playthrough, I was shocked by numerous things I had missed. While some of these situations–such as ripping off Gale’s hand–are only possible if you are playing as The Dark Urge, there were still cellars I had yet to throw myself into, mysteries I had yet to solve, entire conversations I had neglected to start, and several NPCs that I didn’t know I could trick, befriend, piss off, or eliminate in mind-blowing (and/or hilarious) ways. It was only on my second time playing that I discovered there was an entire war that could break out if you don’t assassinate the leaders of the goblin camp, or that you can simply convince some enemies to take their own life and spare yourself a fight. The game’s scope simply seems unfathomable.

And the impact your every action or inaction has in Baldur’s Gate 3 is just as astounding. There were differences in how characters treated my Tiefling versus my Drow. There were severe consequences when my paladin broke her sworn oath, as well as when I entered a relationship with a person one of my party members wasn’t particularly fond of. Whereas games like Mass Effect present you with confined, high-stakes scenarios in which the trajectory of the game can be altered depending upon your choices within a rigid binary, Baldur’s Gate 3 seemingly has no constraints. It feels as though anything can change at any given moment–and there’s a contingency plan for it.

And better yet, Baldur’s Gate 3 also avoids burdening players with an established idea of morality in the same way many choice-driven games do. Sure, your party members will pass judgment based on how you conduct yourself in Faerun, but not a single character is pleased by you simply making every ‘good’ choice, as at times their own interests don’t fall in line with our notion of ‘good.’ This, alongside the fact that none of the dialogue options in Baldur’s Gate 3 are presented as binary, makes for a game that feels more human and subjective. You see this idea take shape throughout the Githyanki storyline. While the Githyanki are demonized by the vast majority of characters you encounter, you get to judge their practices and culture for yourself when you visit their underground settlement. It doesn’t take long for you to understand there is more to Lae’zel and her people than previously thought, but it also doesn’t make it easy to stand by many of their practices or align yourself with their causes.

In Baldur’s Gate 3, you get to decide what companions you keep, your alliances, and ultimately the state of the world and its deities. Eventually, I gave up on save scumming. One, because there were simply too many choices and branching storylines, and two, because every single one of them felt right. I realized it was time to forge my own story, completely unapologetically. And then do it all differently in another playthrough.

I came to a similar conclusion with Tears of the Kingdom. While its style of gameplay doesn’t lend itself to save-scumming and replayability the same way Baldur’s Gate 3 does, I did second guess a lot of what I did and worried that some of my victories were cheap, incorrect, or lacked the same creativity other players demonstrated. In fact, I wrote a feature about these feelings earlier this year, so I’ll spare going into it too much. But suffice to say, Tears of the Kingdom managed to replace my trepidation and anxiety with this sense of empowerment. And that feeling didn’t come from Tears of the Kingdom being the most open of all open-world games, but rather from the value bestowed upon every action you take within it.

Tears of the Kingdom gives you the freedom to go whenever you’d like, in whatever order you’d like, by whatever means possible, and then makes all your decisions feel intentional and legitimate, for lack of a better word. It’s an incredible feat that is definitely aided by how eagerly the game’s developers give you the tools to break the game they created through Link’s various abilities. Ascend, for example, renders certain physical boundaries obsolete, whereas the Fuse mechanic is a playful remedy to what some saw as an irritating hurdle in Breath of the Wild: weapon degradation.

Both Baldur’s Gate 3 and Tears of the Kingdom aren’t afraid to collapse in upon themselves to make room in their respective worlds for a player’s choices. They both gave me the freedom to make my own choices and face their consequences, an endlessly impressive feat that reinforces my favorite aspect of the games that most matter to me.

Credit : Source Post